クラシック音楽への「耳」はどうやって作られるのか?

——人口3%側に行くための、順番の話

音大出身の人と話していると、時々おもしろい瞬間がある。

「いつ、誰の交響曲に“はまったか”」という話題になったときだ。

多くの場合、驚くほど同じ順番が返ってくる。

モーツァルト

ベートーヴェン

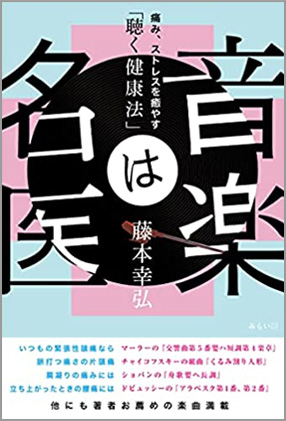

チャイコフスキー

ドヴォルザーク

そして最後に、マーラー。

これは作曲史の話ではない。

聴く側の脳の成長史の話だ。

クラシック音楽が「わかる」人は、なぜ少ないのか

確かにクラシック音楽、特に器楽や交響曲は、人間にとってかなり不親切な音楽だ。

歌詞はない。

拍は曖昧。

盛り上がりは遅い。

情報量は異常に多い。

放っておけば、人はもっと分かりやすい音楽を選ぶ。

だから「クラシックが分かる耳」を持つ人は、体感的に人口の数%しかいない。

これは趣味の問題というより、聴取様式の問題だと思っている。

幼少期に聴いていないと、もう無理なのか?

よく聞かれる質問だ。

答えは

有利ではあるが、決定的ではない。

幼少期にクラシックを聴いていると、長い音楽を聴く耐性や、調性への違和感のなさが自然に身につく。

ただしそれは

「好きになる」ための土台であって、「理解する」ための条件ではない。

構造を追う耳、形式を予測する感覚は、大人になってからでも作れる。

問題は年齢ではなく、通過する順番だ。

耳は才能ではなく、ルートで決まる

クラシック音楽への耳は、才能でも、音感でもない。

どの順番で、どの負荷を、どのタイミングで通過したか。

それだけで決まる。

耳を作るための、現実的な順番

① モーツァルト

最初に必要なのは、音楽が「文」として成立する感覚。

フレーズが短く、終わりが分かり、「次に何が来るか」が予測できる。

ここで「分かる」という快感を、身体に覚えさせる。

② ハイドン/初期ベートーヴェン

音楽が論理で動き始める。

展開、対比、発展。

感情がなくても面白い、という体験が起きる。

ここを通らないと、後の音楽はすべて「雰囲気」になる。

③ シューベルト

構造の中に、人間の感情が滲み出す。

形式は保たれたまま、弱さや孤独が顔を出す。

「音楽が人間になる」最初の地点。

④ チャイコフスキー/ドヴォルザーク

感情を理解した上で浴びる段階。

ここを先にやってしまうと、「泣ける/泣けない」で止まる。

戻るのは難しい。

順番は、本当に大事だ。

⑤ そしてマーラー

音楽が、人生、死、不安、滑稽さ、超越を

すべて同時に引き受ける。

ここまで来ると、音楽は娯楽ではなくなる。

だいたいこの辺が、「3%」の境界線。

マーラーの、その後

マーラーを通過した人の多くは、バッハに回帰し、ラフマニノフに長く滞在する。刺激ではなく、一緒に生きられる音を選ぶようになる。

それは後退ではなく、耐えたあとの選択だ。

結論として

クラシック音楽への耳は才能ではない。

幼少期だけの特権でもない。

どんな順番で、どんな負荷を引き受けたか。

それだけだ。

そして一度できた耳と頭脳は、年齢とともに、静かに、しかし確実に深くなる。

How Is an “Ear” for Classical Music Formed?

— On Sequence, and the Path to the 3 Percent

When I talk with people who studied at music conservatories, there are moments that I find fascinating.

It’s when the conversation turns to “When did you first get hooked on whose symphony?”

More often than not, the answers come back in a surprisingly similar order:

Mozart

Beethoven

Tchaikovsky

Dvořák

And finally, Mahler.

This is not a story about the history of composition.

It’s a story about the developmental history of the listener’s brain.

Why Are There So Few People Who “Understand” Classical Music?

Classical music—especially instrumental works and symphonies—is, frankly, not very kind to the human brain.

There are no lyrics.

The beat is ambiguous.

The climax comes late.

The amount of information is overwhelming.

Left to their own devices, people naturally choose music that is easier to grasp.

That’s why, in practical terms, only a few percent of the population seem to possess what we might call “an ear for classical music.”

I don’t think this is a matter of taste so much as a matter of listening mode.

If You Didn’t Hear It as a Child, Is It Too Late?

This is a question I’m often asked.

The answer is:

It helps—but it’s not decisive.

Listening to classical music in childhood builds a natural tolerance for long-form music and a comfort with tonality.

But that is merely the foundation for liking classical music, not a prerequisite for understanding it.

An ear that can follow structure, and a sense that can anticipate form, can absolutely be developed in adulthood.

The real issue isn’t age—it’s the order of passage.

An Ear Is Not Talent. It’s a Route.

An ear for classical music has nothing to do with innate talent or perfect pitch.

What matters is the sequence in which you pass through certain musical loads, and at what timing.

That alone determines everything.

A Realistic Sequence for Building the Ear

1. Mozart

What’s needed first is a sense that music functions as a “sentence.”

The phrases are short, the endings are clear, and you can predict what comes next.

Here, the body learns the pleasure of understanding.

2. Haydn / Early Beethoven

Music begins to move by logic.

Development, contrast, transformation.

You discover that music can be interesting even without overt emotion.

If you skip this stage, everything that follows becomes mere “atmosphere.”

3. Schubert

Human emotion begins to seep into the structure.

The form remains intact, yet fragility and loneliness emerge.

This is the first point at which “music becomes human.”

4. Tchaikovsky / Dvořák

Now you immerse yourself in emotion—but with understanding.

If you come here too early, listening stops at “does it make me cry or not.”

It’s very hard to go back after that.

Sequence truly matters.

5. And Then, Mahler

Music takes on life, death, anxiety, absurdity, and transcendence—

all at once.

At this point, music ceases to be mere entertainment.

This is roughly where the boundary of the “3 percent” lies.

After Mahler

Many who pass through Mahler eventually return to Bach and spend long periods with Rachmaninoff.

They stop choosing music for stimulation, and begin choosing sounds they can live alongside.

This isn’t regression—it’s a choice made after endurance.

In Conclusion

An ear for classical music is not a talent.

It’s not a privilege reserved for childhood.

What matters is the sequence you followed, and the weight you chose to bear.

That’s all.

And once formed, that ear and mind continue to deepen quietly—but unmistakably—with age.