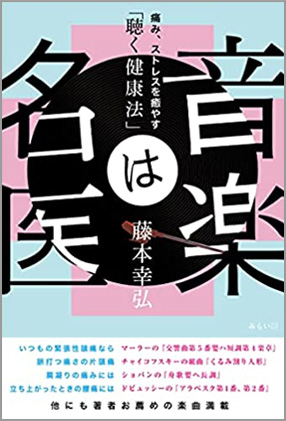

夜にふとした事から小澤征爾の《春の祭典》のおそらくボストン交響楽団の動画にハマり、しばらく観入ってしまった。

ストラヴィンスキーの《春の祭典》は拍子が頻繁に変わり、アクセントがずれ、同時に複数のリズムが走るという、いわば指揮者殺しの楽譜。

多くの指揮者は「拍を正確に示す」ことで、なんとか体裁を整えてまとめに行く。

しかし小澤は違う。小澤の指揮はリズムを外から管理しないで中から湧かせる感じ。

全ての楽譜を頭の中に入れて、全く譜面を見ない。音がまさに“原始的な衝動”として立ち上がる。

これが小澤征爾の凄さなんだなあ。

One evening, almost by chance, I fell into watching a video of Seiji Ozawa conducting The Rite of Spring—most likely with the Boston Symphony Orchestra—and found myself completely absorbed for quite a while.

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is a score notorious as a kind of “conductor-killer”: the meter changes constantly, accents are displaced, and multiple rhythms surge forward simultaneously.

Many conductors manage to hold it together by focusing on “clearly indicating the beat,” somehow giving the performance a coherent shape.

But Ozawa is different. His conducting doesn’t control rhythm from the outside; it feels as though the rhythm wells up from within.

He has the entire score in his head and never looks at the music. The sound rises up as a truly “primitive impulse.”

This, I think, is what makes Seiji Ozawa so extraordinary.