夜の草むらに響くシンフォニー ― 虫の声のオーケストレーション

帰国したら一気に秋になっていた。

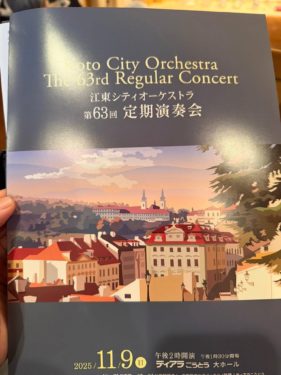

昨晩、コンサート帰りにほろ酔いで歩いていると、どこからともなく「リーン、リーン」という秋の調べが聞こえてくる。

耳を澄ませば、その背後には低く響く「ギーッギーッ」という低音と、かすかな「チンチロリン」という高音。

思えば古来、日本人は虫の声を“noise(雑音)”ではなく“music(音楽)”として聴いてきた。

西洋の人々が夜の虫を「静寂を破る音」と感じるのに対し、私たちは「静寂を彩る音」として心の内に受け入れてきた。

これは、脳の可塑性と文化的聴覚の融合が生んだ感性だろう。

まるでそれぞれが音域を分担しながら、夜の森全体をひとつのオーケストラとして演奏しているようだ。

■ 自然が生み出した音の「棲み分け」

実際、この響きの秩序には科学的な裏づけがある。

生態学には「音響ニッチ仮説(Acoustic Niche Hypothesis)」という概念があり、昆虫たちは互いの鳴き声が重ならないように、進化の過程で周波数帯を棲み分けてきたとされる(Riede, Journal of Animal Ecology, 1997, pp. 879–892)。

スズムシは6〜8kHzの澄んだ高音、コオロギは3〜6kHzの中音、

そしてクツワムシは2〜3kHzの低音を担当する。

これにより、同じ夜空の下でも彼らの声は混ざり合うことなく、立体的に響く。

自然界が作曲した「多声的生態系」——まさにそれは、生命の調和そのものだ。

■ 聴く側の脳が生む「調和」の幻影

さらに興味深いのは、人間の脳がこの音の重なりを“和音”として感じることだ。

京都大学の神経科学の研究(Takahashi et al., Neuroscience Letters, 2009, pp. 112–118)によると、倍音構造をもつ自然音を聴くと、脳の前頭連合野が“快”の感覚を伴って反応するという。

つまり、虫たちが無意識に奏でる声のハーモニーは、私たちの脳が「美しい」と感じる構造に偶然にも一致しているのである。

■ 音の生態系としての夜

夜の虫の合唱は、単なる音の重なりではない。

カネタタキの短い打音はリズムを刻み、スズムシは旋律を紡ぎ、クツワムシが低音の土台を支える。

それはバイオリン、フルート、チェロの関係に似ている。

さらにこの重層構造は、捕食者に対しての“音のカモフラージュ”としても機能する(Narins et al., Proc. R. Soc. B, 2004, pp. 125–132)。

つまり、自然界の音楽には、美しさと防御の二重構造があるのだ。

■ 結語 ― 自然という作曲家

虫たちは進化の中で、互いの声を聴きながら棲み分けを繰り返し、やがて「重ならない音の世界」を作り上げた。

それを調和として感じ取る人間の脳——。

この両者の間にある共鳴こそ、生命の音楽と呼ぶにふさわしい。

夜風が通り抜けるたび、音の層がわずかに揺れる。

それはまるで、自然という作曲家が指揮棒をそっと振るう瞬間のように思えた

。

。

A Symphony Resonating in the Night Grass — The Orchestration of Insect Voices

When I returned home, autumn had already arrived.

Last night, slightly tipsy after a concert, I was walking when I began to hear a faint “leen, leen” — the song of autumn — drifting from somewhere unseen.

As I listened more closely, I noticed a low “gee-gee” humming beneath, and a delicate “chin-chiro-rin” twinkling above it all.

It struck me that, since ancient times, the Japanese have not heard insect sounds as noise but as music.

While people in the West might perceive these nocturnal chirps as “sounds that disturb the silence,” we have come to accept them as “sounds that color the silence.”

Perhaps this sensibility was born from the fusion of neural plasticity and the cultural shaping of our hearing.

It is as if each insect takes on a specific tonal range, performing together as a single orchestra of the nocturnal forest.

The Natural Partitioning of Sound

In fact, there is a scientific basis for this order in sound.

In ecology, there is a concept called the “Acoustic Niche Hypothesis.”

It proposes that, through evolution, insects have come to occupy distinct frequency ranges so their calls do not overlap (Riede, Journal of Animal Ecology, 1997, pp. 879–892).

The bell cricket (suzumushi) sings in clear high tones around 6–8 kHz,

the field cricket (koorogi) in the middle range of 3–6 kHz,

and the katydid (kutsuwa-mushi) in the low range of 2–3 kHz.

Thus, even under the same night sky, their voices blend without interference, resonating in three dimensions.

It is a polyphonic ecosystem composed by nature itself — a true harmony of life.

The Illusion of Harmony Created by the Listener’s Brain

Even more fascinating is that the human brain perceives this layering of sounds as harmony.

According to a neuroscience study from Kyoto University (Takahashi et al., Neuroscience Letters, 2009, pp. 112–118),

when we listen to natural sounds that contain harmonic structures, the prefrontal cortex responds with sensations of pleasure.

In other words, the harmony unconsciously produced by insects happens to coincide with the very structure our brains interpret as “beautiful.”

The Night as an Acoustic Ecosystem

The chorus of insects at night is more than a mere overlap of sounds.

The clicking of the kanetataki keeps rhythm,

the suzumushi weaves melody,

and the kutsuwa-mushi supports it all with a deep, resonant foundation.

Their relationship is like that of violins, flutes, and cellos in an orchestra.

Moreover, this multilayered soundscape functions as an acoustic camouflage against predators (Narins et al., Proc. R. Soc. B, 2004, pp. 125–132).

Thus, the music of nature embodies both beauty and defense — an elegant dual structure.

Epilogue — Nature, the Composer

Through countless generations, insects have evolved by listening to one another, dividing their sonic space, and eventually creating a world of sounds that never overlap.

And humans, in turn, perceive that separation as harmony.

The resonance that arises between these two — the insects and our own perception — is nothing less than the music of life.

Each time the night breeze passes, the layers of sound tremble ever so slightly.

It feels as though the great Composer called Nature is gently lifting its baton to conduct the symphony once more.