なぜ『オペラ座の怪人』はオペラではなく、ミュージカルとして生まれたのか

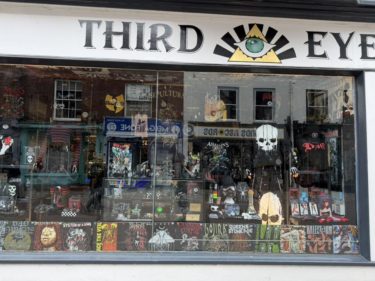

ロンドン最後の夜。His Majesty’s Theatreに大好きなミュージカル「オペラ座の怪人」を観にきました。

2022年9月8日、エリザベス2世が崩御し、チャールズ3世が即位して、Her Majesty’s Theatre(女王陛下の劇場)だった名称が、His Majesty’s Theatre(国王陛下の劇場)へと変更されたのです。

このミュージカルはそれこそ20回以上観ているでしょうか。劇場の名前が変わってからは初めてかもしれません。今はニューヨークでも観られなくなってしまったんですよね。本当に音楽が素晴らしく、舞台も豪華、ストーリーも大好きですが、久しぶりに観ると圧倒されますね。

客席に座り、開演前の静寂の中で天井を見上げていると、ふと奇妙な感覚に包まれます。この劇場で上演されている作品は、題名に「オペラ座」とありながら、実はオペラではない。これは単なる名称の問題ではなく、19世紀から20世紀にかけて起きた音楽の「主役交代」を象徴する事件なのです。

オペラとは本来、「声が主役」の芸術でした。モーツァルト、ヴェルディ、ワーグナー。彼らの作品では、音楽の中心は常に声であり、オーケストラはその精神を支える「身体」の役割を担っていました。声は神に最も近い音であり、劇場は神殿でした。オペラ歌手は単なる演者ではなく、神話の媒介者だったのです。

しかし19世紀後半になると、都市の構造そのものが変わり始めます。産業革命によって中産階級が誕生し、芸術は貴族のための儀式から、市民のための体験へと変化しました。ここで決定的な変化が起きます。「声」から「物語」へと、重心が移動したのです。

オペラでは、時間は止まります。有名なアリアの瞬間、物語は進行を停止し、登場人物の内面が永遠のように引き伸ばされる。例えば《椿姫》の「Sempre libera」では、ヴィオレッタは物語の中にいながら、時間の外側に立っています。これは現実の時間ではなく、精神の時間です。

一方でミュージカルでは、時間は止まりません。音楽は物語を前進させるための推進力として機能します。『オペラ座の怪人』の「The Music of the Night」は美しい旋律ですが、それは単なる心理描写ではなく、クリスティーヌを地下へ導く「力」そのものです。音楽が時間を止めるのではなく、空間を変形させるのです。

ここに、決定的な違いがあります。

オペラは垂直的な芸術です。神へ向かう運動。上昇する音。超越への志向。一方でミュージカルは水平的な芸術です。都市の中を移動し、地下へ降り、再び地上へ戻る。これは近代都市そのものの構造です。

『オペラ座の怪人』の舞台はパリ・オペラ座ですが、その本質はオペラではなく、「地下構造」にあります。ファントムは地下に住んでいます。彼は舞台の上ではなく、都市の下に存在する。これは象徴的です。19世紀のオペラが天上を志向したのに対し、20世紀の芸術は地下を発見したのです。

医学的に言えば、これは大脳皮質から辺縁系への重心移動です。オペラは前頭葉の芸術です。理性、構造、美。しかしミュージカルは辺縁系の芸術です。情動、記憶、欲望。『オペラ座の怪人』が世界中の観客に直感的に理解されるのは、それが理性ではなく、より古い脳に直接作用するからです。

アンドリュー・ロイド=ウェバーは、この構造を本能的に理解していました。彼はワーグナーのように神話を描こうとはしなかった。代わりに、「都市そのもの」を神話に変えたのです。地下に住む音楽家。顔を隠した天才。理解されない愛。これはギリシャ神話ではなく、近代都市が生んだ新しい神話です。

『オペラ座の怪人』は単なる恋愛劇ではありません。あれは、人間の存在の構造そのものを描いた作品です。怪人は怪物だから地下に住んでいるのではありません。愛されなかったから地下に住むしかなかったのです。

彼は音楽という、宇宙の秩序に最も近い言語を理解する知性を持ちながら、その肉体の外見ゆえに社会から排除されました。つまり彼は、「理解する能力」と「理解されない運命」の両方を同時に背負った存在です。この構造は、程度の差こそあれ、すべての人間の内部に存在します。

考えてみれば、現代の我々も同じ構造の中に生きています。地上では理性的な社会生活を送りながら、地下では誰にも見せない情動が蠢いている。ファントムとは、我々自身の深層構造の投影なのです。

だからこそ、この作品はオペラではなく、ミュージカルとして生まれなければならなかった。オペラという形式では、この「地下」は描けなかったのです。ミュージカルという、より柔軟で都市的な形式だけが、この物語を成立させることができた。

ロンドンの夜、劇場を出ると、石畳の下に地下鉄が走っています。誰もその存在を意識しません。しかし都市は、その地下構造によって支えられている。怪人がニューヨークのコニーアイランドに居を移したLove Never Diesという続編もありますが、ファントムは、消えたのではありません。彼は今も、都市の下で音楽を書き続けているのでしょうね。

Why The Phantom of the Opera Was Born as a Musical, Not an Opera

On my final night in London, I went to see my beloved musical The Phantom of the Opera at His Majesty’s Theatre.

On September 8, 2022, Elizabeth II passed away, and Charles III ascended the throne. As a result, the venue’s name changed from Her Majesty’s Theatre to His Majesty’s Theatre.

I have probably seen this musical more than twenty times. It may have been my first visit since the theatre’s name changed. It is no longer running in New York, after all. The music is magnificent, the staging lavish, and I love the story deeply — yet watching it again after some time, I was overwhelmed anew.

Sitting in the audience before the curtain rose, gazing at the ceiling in the pre-performance silence, I felt a curious sensation. The work being staged here contains the word “Opera” in its title — yet it is not an opera. This is not merely a matter of terminology. It symbolizes a historical shift in music from the 19th to the 20th century — a change of protagonist.

Opera was originally an art in which the voice was sovereign. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Giuseppe Verdi, Richard Wagner — in their works, the voice was always central, while the orchestra served as the “body” supporting its spirit. The human voice was the sound closest to God; the theatre was a temple. Opera singers were not merely performers, but mediators of myth.

By the late 19th century, however, the very structure of cities began to change. The Industrial Revolution gave birth to the middle class, and art shifted from an aristocratic ritual to a civic experience. At that moment, a decisive transformation occurred: the center of gravity moved from voice to story.

In opera, time stops. During a famous aria, the narrative halts, and the character’s inner life is stretched toward eternity. In La Traviata, for example, during “Sempre libera,” Violetta stands outside chronological time. It is not real time, but psychological time.

In musical theatre, by contrast, time does not stop. Music functions as propulsion, advancing the narrative. In The Phantom of the Opera, “The Music of the Night” is a beautiful melody — but it is not merely psychological expression. It is the very force that draws Christine underground. Music does not suspend time; it transforms space.

Here lies the decisive difference.

Opera is vertical art — movement toward the divine, ascending sound, transcendence. Musical theatre is horizontal art — moving through the city, descending underground, returning to the surface. It mirrors the structure of the modern metropolis.

Though set in the Paris Opera House, the essence of The Phantom of the Opera lies not in opera itself, but in its subterranean structure. The Phantom lives underground. He does not inhabit the stage above, but the city below. This is symbolic. While 19th-century opera aspired toward heaven, 20th-century art discovered the underground.

If I may borrow a medical metaphor, this is a shift from the cerebral cortex to the limbic system. Opera is the art of the frontal lobe: reason, structure, beauty. Musical theatre is the art of the limbic system: emotion, memory, desire. The reason The Phantom of the Opera resonates so intuitively with global audiences is that it speaks not to rationality, but to an older brain.

Andrew Lloyd Webber understood this instinctively. He did not attempt to write myth in the Wagnerian sense. Instead, he transformed the city itself into myth. A musician living underground. A genius hiding his face. Love that cannot be understood. This is not Greek mythology; it is a new mythology born of the modern city.

The Phantom of the Opera is not merely a romance. It depicts the very structure of human existence. The Phantom does not live underground because he is a monster; he lives underground because he was never loved.

He possesses the intelligence to understand music — a language closest to the order of the universe — yet he is excluded from society because of his physical appearance. He embodies both the capacity to understand and the destiny of being misunderstood. In varying degrees, this structure exists within all of us.

Modern life reflects the same duality. On the surface, we live rational social lives. Beneath that surface, unseen emotions stir. The Phantom is a projection of our own deep structure.

That is why this work had to be born as a musical, not an opera. The operatic form could not have depicted this “underground.” Only the more flexible, urban form of musical theatre could sustain this narrative.

When you leave the theatre at night in London, the Underground runs beneath the cobblestones. Few people consciously notice it. Yet the city is supported by its subterranean structure.

The Phantom was later imagined to have moved to Coney Island in the sequel Love Never Dies. But he has not vanished. He is still there — somewhere beneath the city — writing music in the dark.