London cityscape

藤本幸弘オフィシャルブログ

藤本幸弘オフィシャルブログ

London cityscape

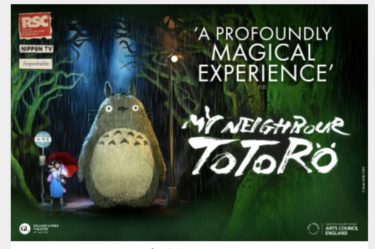

2023年のウエストエンド公演で大成功を収めた『となりのトトロ』が、2025年3月8日よりロンドンのジリアン・リン劇場で期間限定公演として待望の再演を迎えています。

『となりのトトロ』はWhatsOnStageアワードを5部門受賞、そして驚異の9部門でオリヴィエ賞にノミネートされていました。まだチケットあるようなので、滞在中に観に行こう。とはいえ、ウエストエンドは観てみたい色々なミュージカルがあるので迷います。

After its triumphant run in 2023, the stage adaptation of My Neighbour Totoro has made its long-awaited return to London for a limited season at the Gillian Lynne Theatre, starting March 8, 2025.

Having scooped five WhatsOnStage Awards and an incredible nine Olivier Award nominations, it’s a must-see. It looks like tickets are still available, so I’m thinking of catching a performance during my stay. That said, with so many amazing musicals to choose from in the West End, it’s hard to decide!

日本もそろそろカーボンニュートラル戦略を破棄すべきではないか?

海外にいると、Google検索の結果さえ日本とは異なる世界を見せてくれます。その中で目に止まったのが、英国保守党党首 Kemi Badenoch が、政権を奪還した場合に Climate Change Act 2008 を廃止すると表明したという報道でした。

“vows to repeal Climate Change Act”。

2008年制定の同法は、法的拘束力を持つ長期排出削減目標を定めた、世界初の包括的気候立法でした。気候政策の歴史におけるマイルストーンであったことは間違いありません。しかし、歴史的であることと、永続的であることは同義ではない。

1997年、京都で採択された Kyoto Protocol は、温室効果ガス削減に法的拘束力を持たせた最初の国際合意でした。理想を制度に落とし込んだ、歴史的な一歩です。日本では2002年に小泉純一郎時代に批准されました。しかしその制度は、同時に構造的な限界を抱えていました。最大の問題は、主要排出国の米国や中国、インドなどの足並みが揃わなかったことです。削減義務を負う国と負わない国が分かれ、世界全体の排出量は増え続けました。環境は守りたい。しかし国益も守らなければならない。つまりは「理想の制度」。この構図が、制度の持続性を揺さぶりました。

排出削減は理念ではなく、現実の経済活動の中で行われます。そしてそれは必ずコストを伴います。

電力価格の上昇は、単なる家計の問題ではありません。研究開発費、医療機関の運営コスト、データセンターの電源、製造業の設備投資。

国家の生産力そのものに直結します。

欧州では産業用電力価格が米国より高い水準にあり、エネルギー多消費産業の投資判断に影響を与えています。エネルギーは単なる資源ではなく、競争力そのものです。

英国の世界排出量に占める割合は約1%。日本は約3%です。ここに、冷徹な算術があります。国内で大きな負担を課したとき、そのコストは世界全体の排出削減にどれほど影響するのか。これは理念ではなく、構造の問題です。

英国保守党の主張は、脱炭素の放棄ではありません。順序の再設計です。まず、安価で安定したエネルギー供給を確立する。次に、経済成長と技術革新を促進する。その結果として、排出削減を実現する。これは規制主導から、技術主導への転換とも言えます。

日本はエネルギー自給率が低く、電力依存型産業構造を持つ国家です。2050年カーボンニュートラルは国家目標ですが、その達成手段は国家の競争力に直接影響します。経済が弱体化すれば研究は停滞します。研究が停滞すれば技術革新も止まります。技術が止まれば、世界の排出削減に寄与する力も失われます。

京都議定書は理想の象徴でした。しかし四半世紀を経たいま問われているのは、理念を守ることそのものではありません。脱炭素を信念として維持するのか。それとも国家戦略として再設計するのか。

理想と現実。

倫理と工学。

環境と経済。

その均衡点を、冷静に、定量的に見つめ直す時期に来ています。気候政策とは、環境問題であると同時に、国家の存続戦略そのものだからです。まあ天下り団体や利権団体の多い日本では、難しいのでしょうけれど、諦めずにやっていただきたいですね。

Is It Time for Japan to Scrap Its Carbon Neutrality Strategy?

When traveling abroad, even Google search results reveal a world different from the one seen in Japan. One report that caught my eye was that Kemi Badenoch, leader of the British Conservative Party, vowed to repeal the Climate Change Act 2008 should her party return to power.

“Vows to repeal Climate Change Act.”

Enacted in 2008, this law was the world’s first comprehensive climate legislation to set legally binding long-term emission reduction targets. It was undoubtedly a milestone in the history of climate policy. However, being historic is not synonymous with being permanent.

In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was adopted as the first international agreement to make greenhouse gas reductions legally binding. It was a historic step that translated ideals into a formal system. Japan ratified it in 2002 under the Koizumi administration. Yet, that system carried inherent structural limitations. The greatest issue was the lack of alignment among major emitters like the United States, China, and India. With countries split between those with reduction obligations and those without, global emissions continued to rise. The desire to protect the environment clashed with the necessity of protecting national interests. In short, it was an “idealized system,” and this friction has shaken its long-term viability.

Emission reduction is not a mere philosophy; it occurs within the realm of real economic activity, and it always incurs a cost.

Rising electricity prices are not just a household issue. They impact R&D expenditures, the operating costs of medical institutions, power for data centers, and capital investment in manufacturing.

Energy costs are directly linked to a nation’s productive capacity.

In Europe, industrial electricity prices remain higher than in the U.S., influencing investment decisions in energy-intensive industries. Energy is not just a resource; it is competitiveness itself.

The UK accounts for about 1% of global emissions; Japan accounts for about 3%. Here lies a cold arithmetic: if a nation imposes a massive domestic burden, how much will that cost actually impact global emission reductions? This is a question of structure, not ideology.

The argument from the British Conservatives is not an abandonment of decarbonization, but a redesign of priorities. First, establish an affordable and stable energy supply. Second, promote economic growth and technological innovation. As a result, emission reductions will follow. This represents a shift from regulation-driven policy to technology-driven progress.

Japan is a nation with low energy self-sufficiency and a power-dependent industrial structure. While Carbon Neutrality by 2050 is a national goal, the means of achieving it directly impact national competitiveness. If the economy weakens, research stagnates. If research stagnates, technological innovation stops. If technology stops, we lose the power to contribute to global emission reductions.

The Kyoto Protocol was a symbol of idealism. But a quarter-century later, the question is no longer about clinging to that philosophy. The question is: do we maintain decarbonization as a matter of faith, or do we redesign it as a national strategy?

Ideals vs. Reality.

Ethics vs. Engineering.

Environment vs. Economy.

The time has come to reconsider the equilibrium point—calmly and quantitatively. Climate policy is an environmental issue, but it is also, fundamentally, a strategy for national survival. Given the density of “Amakudari” (golden parachute) organizations and vested interests in Japan, this may be a difficult task—but it is one I hope we do not give up on.

テート・ブリテンへ

ロンドンで好きな美術館のひとつ、Tate Britainへ行きました。セントジェームズから南に向かって歩きます。いつもの動線とは逆方向なので、なぜか少し遠く感じますがそれでも歩いて向かうのが好きです。テムズ川沿いの空気を吸いながら近づいていく時間が、ちょうどよい準備運動になります。

ここに来る理由は明確です。J. M. W. Turnerの作品が数多く所蔵されているからです。

イギリス人のターナーは、「風景画家」という言葉では少し足りない気がします。僕には、フェルメールの次に光の運動を描いた実験者のように思えます。欧州各地を旅し、自然の崇高を追い求めながら、同時に産業革命という時代の転換点も画面に取り込んでいきました。蒸気や煙、速度感。自然とテクノロジーが同じキャンバスの上でせめぎ合っています。

晩年の作品になると、形はほとんど溶けていきます。輪郭は曖昧になり、光そのものが主役になります。後のClaude Monetに影響を与えたといわれるのも納得できます。ロンドンの霧を描いたモネの画面の奥に、ターナーの気配が感じられます。

僕が特に好きなのは、モン・サン=ミシェルを描いた作品です。

海と空の境界が溶け合い、修道院のシルエットが光の中に浮かび上がっています。対象を克明に描くというよりも、光の中で対象がどのように揺らぐのかを描いている印象です。その曖昧さが、とても心地よいのです。

今回の展示では、ヴァチカンを主題にした大きな作品もありました。今回気づいたのですが、その中央に、Raphaelの《小椅子の聖母》が描かれていました。原作はフィレンツェのPalazzo Pittiに所蔵されています。

円形の画面の中で、聖母と子供が静かに抱き合っている構図。ターナーが光を拡散させる画家だとすれば、ラファエロは形を完璧に統御する画家です。方向性は対照的ですが、どちらも極限まで完成された世界です。

僕はこの絵が好きで、以前、油彩で模写を描いてもらった事があり、その絵はいまもクリニックFの5階のレーザー室に飾っています。診療の合間にふと目を向けると、あの静かな円環がそこにあります。光が揺らぐ世界と、形が閉じる世界。その両方を行き来できることが、僕にとっての贅沢なのかもしれません。

テート・ブリテンは、そんな時間を与えてくれる場所です。

A Visit to Tate Britain

I visited Tate Britain, one of my favorite art galleries in London. I walked south from St. James’s—a route that feels slightly longer than usual as it’s the opposite of my typical path, yet I always prefer approaching it on foot. Breathing in the air along the River Thames serves as the perfect warm-up for the mind.

My reason for coming here is clear: the extensive collection of works by J.M.W. Turner.

For me, calling the British master Turner a “landscape painter” feels insufficient. I see him as an experimentalist of light, second only to Vermeer. As he traveled across Europe in pursuit of the “Sublime” in nature, he simultaneously captured the turning point of the Industrial Revolution on his canvases. Steam, smoke, and a sense of velocity—nature and technology contend within the same frame.

In his later years, forms began to dissolve. Outlines became blurred, and light itself became the protagonist. It is easy to see why he is said to have influenced Claude Monet. Behind the hazy London fog in Monet’s paintings, one can sense the lingering presence of Turner.

I am particularly fond of his depiction of Mont Saint-Michel. The boundary between sea and sky melts away, leaving the silhouette of the abbey floating within the light. Rather than meticulously detailing the subject, he captures how the subject flickers and wavers within the light. That ambiguity is incredibly soothing.

In this exhibition, there was also a large-scale work themed around the Vatican. I noticed something new this time: at its center, he had painted Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiola (Madonna of the Chair). The original is housed in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence.

The composition features the Virgin and Child in a quiet embrace within a tondo (circular) frame. If Turner is a painter who diffuses light, Raphael is a painter who exerts perfect control over form. Their directions are polar opposites, yet both represent worlds refined to their absolute limit.

I have always loved this painting and once commissioned an oil copy of it, which now hangs in the 5th-floor laser room of Clinic F. When I catch a glimpse of it between consultations, that quiet, sacred circle is always there. The world where light wavers and the world where form is contained—perhaps being able to traverse between the two is my greatest luxury.

Tate Britain is a place that grants me that kind of time.

雨が上がったので、セントジェームズからテートブリテンまでロンドン散歩。大英博物館でサムライ展やってる様です。明日行ってみよう。

The rain has cleared up, so I’m taking a stroll from St. James to Tate Britain. It looks like the British Museum is holding a Samurai exhibition—I think I’ll head there tomorrow.