憲法をめぐる議論は、賛否が先に立ちがちです。しかし冷静に比較すると、日本国憲法の特徴は「善悪」ではなく「設計思想の違い」にあります。

① 戦争放棄を明記している

日本国憲法第9条は、戦争放棄と戦力不保持を明記しています。多くの国は「自衛権」を当然の前提としますが、日本は軍事を強く抑制する条文を持つ。ここは世界でもかなり特殊です。

② 一度も改正されていない

1947年施行以来、改正ゼロ。例えばドイツ連邦共和国基本法は60回以上改正、アメリカ合衆国憲法も27回改正。日本は「極めて硬い憲法」に分類されます。

③ 条文と現実の乖離

条文は「戦力不保持」。しかし現実には高度な自衛隊が存在する。多くの国では条文と実態が概ね一致しますが、日本は「解釈」によって運用してきました。条文よりも解釈が先行する構造です。

④ 非常事態条項がない

多くの国には、戦争や国家危機の際に権限を集中させる非常事態条項があります。日本国憲法には包括的な緊急権規定がない。危機時も基本的に平時と同じ統治構造で対応する設計です。

理想主義的で抑制的な設計である一方、柔軟性と明確性に課題を抱えている。憲法は「戦争を物理的に止める装置」ではありません。しかし、権力を縛る装置ではあります。問題は条文そのものよりも、それをどう運用し、どう責任を取る構造にするかです。

ドイツ

ドイツ連邦共和国基本法には「緊急事態条項(Notstandsgesetze)」があります。

武力攻撃時に連邦政府へ権限集中。連邦軍の国内出動を可能にする。通信の制限や移動制限が可能。立法手続の簡略化。ただし「人間の尊厳」などは制限不可(永遠条項)。

フランス

フランス共和国憲法第16条。国家の独立や領土が重大危機にある場合。大統領が広範な非常権限を行使可能。議会を迂回して命令を出せる。テロ事件後に実際に発動されました。

アメリカ

アメリカ合衆国憲法には明確な包括条項はないが、反乱時の人身保護令状停止(Article I, Section 9)大統領のCommander in Chief権限さらに法律(国家非常事態法)で広範権限により実質的な緊急対応が可能。

韓国

大韓民国憲法。戒厳令の明記。大統領の緊急命令権。軍事クーデターの歴史を踏まえつつ制度化。

日本は?

日本国憲法には、戦争・内乱・大規模災害時の包括的緊急権条項は存在しない。国会機能停止時の明確な代替規定も弱い。

コロナ禍でも「法律」で対応し、憲法上の緊急条項は使われませんでした。

世界の社会経済構造も全て進化する時代に解釈のみで対応してきた日本ですが、変化しない憲法によって、国の進化を止められてしまうのではないかと思いますね。

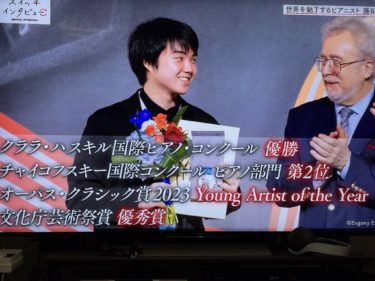

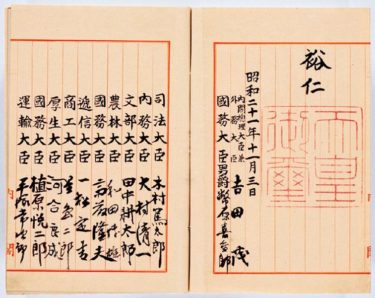

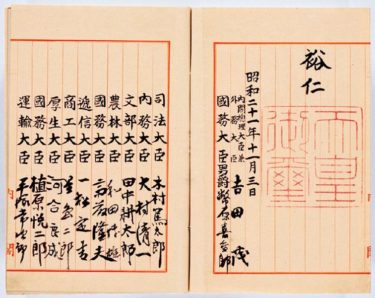

写真は国立公文書館にある日本国憲法の写真です。

“How Is the Constitution of Japan Different from Other Constitutions Around the World?”

Debates over the Constitution often become polarized into “for” or “against.” But when we examine it calmly and comparatively, the distinctive features of the Constitution of Japan lie not in questions of good or bad, but in differences in constitutional design philosophy.

- Explicit renunciation of war

Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan clearly renounces war and the maintenance of armed forces. Most countries take the “right of self-defense” as a given, but Japan includes a clause that strongly restrains military power. In global terms, this is quite unusual.

- Never amended

Since its enforcement in 1947, it has never been amended. By comparison, the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany has been amended more than 60 times, and the Constitution of the United States of America has been amended 27 times. Japan is classified as having an “extremely rigid” constitution.

- Gap between text and reality

The text states “no war potential shall be maintained.” Yet in reality, Japan possesses highly advanced Self-Defense Forces. In many countries, constitutional text and actual practice broadly align. In Japan, however, governance has relied heavily on interpretation. In effect, interpretation has taken precedence over the literal wording.

- No comprehensive emergency clause

Many countries include emergency provisions that concentrate authority during war or national crisis. The Constitution of Japan has no comprehensive emergency powers clause. Even in times of crisis, the system is designed to function largely under the same governing structure as in peacetime.

Thus, while the Constitution reflects an idealistic and highly restrained design, it also faces challenges in flexibility and clarity. A constitution is not a device that physically stops war. It is, however, a device that restrains power. The issue is not merely the wording itself, but how it is implemented and what structures of accountability accompany it.

Germany

The Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany includes emergency provisions (Notstandsgesetze).

- Authority can be concentrated in the federal government during armed attack.

- The federal armed forces may be deployed domestically.

- Communications and movement can be restricted.

- Legislative procedures can be simplified.

However, certain principles—such as human dignity—cannot be limited (the so-called “eternity clause”).

France

Article 16 of the Constitution of the French Republic provides that when the independence of the nation or its territory faces grave danger, the President may exercise broad emergency powers.

- The President may issue orders bypassing Parliament.

These powers were actually invoked following major terrorist attacks.

United States

The Constitution of the United States of America does not contain a single comprehensive emergency clause. However:

- Habeas corpus may be suspended in cases of rebellion (Article I, Section 9).

- The President holds authority as Commander in Chief.

- Federal statutes, such as the National Emergencies Act, provide broad practical emergency powers.

South Korea

The Constitution of the Republic of Korea explicitly provides for martial law and grants the President emergency decree powers. These were institutionalized in light of the country’s history of military coups.

And Japan?

The Constitution of Japan contains no comprehensive emergency powers clause covering war, internal conflict, or large-scale disaster. Provisions addressing situations in which the Diet cannot function are also limited.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, Japan responded primarily through legislation, without invoking any constitutional emergency provisions.

At a time when global socio-economic structures are evolving rapidly, Japan has relied on constitutional interpretation to adapt. Yet one may wonder whether a constitution that does not itself evolve could eventually constrain the nation’s development.

The photograph shows the Constitution of Japan preserved at the National Archives of Japan.