そういえば帰国後の写真がなかったので、スタッフが撮ってくれました。こちらもiPhone 17 pro MAXで相撮。ひるんでました。笑。

Didn’t have any post-return photos, so the staff took one for me!

Shot on iPhone 17 Pro Max (again).

I totally froze up in front of it lol

藤本幸弘オフィシャルブログ

藤本幸弘オフィシャルブログ

そういえば帰国後の写真がなかったので、スタッフが撮ってくれました。こちらもiPhone 17 pro MAXで相撮。ひるんでました。笑。

Didn’t have any post-return photos, so the staff took one for me!

Shot on iPhone 17 Pro Max (again).

I totally froze up in front of it lol

ーーー昭和っぽいとは?ーーー

2025年は昭和100年にあたる年でした。

今年の企画として、昭和100年史をさかのぼる会を7度も開催してきて、本日18時からが、その最終日となります。

1995年から2025年までの現代まで。一気に30年を扱います。

個人的には、記念すべき年に、日本という国家の成り立ちを再度、調べ、学ぶことができ、非常に有益でした。コロナ大過や、日米地位協定、ディープステートといったワードも、より深く理解することができました。

第一次世界大戦後、国際連盟に加入し、日本が世界の大国と認められるようになった頃に昭和が始まりましたが、100年となると世代も大きく変わり、変化も多々ありますよね。

今も「昭和っぽい」という言葉がありますが、いったいどういうのが昭和の概念だったのでしょうか?

少し考えてみました。

一、理不尽への耐性と「我慢の美学」

昭和の人々は、理不尽を受け入れ、耐えることを「強さ」と信じた世代でした。

会社では上司の怒号、学校では竹刀、家庭では沈黙。だがその背景には「社会の歯車として生き抜く」という共通の覚悟があった。

「理不尽は、鍛錬の一形態である」

そう信じて働いた人々の背中に、日本のインフラと技術は築かれた。

この「我慢の文化」は、現代では否定されがちですが、実は社会秩序を支えた心理的免疫でもありました。

二、勤勉と共同体 ― 「24時間戦えますか」

昭和のサラリーマンは、まさに“企業戦士”と呼ばれた。

家庭より会社が優先され、「終身雇用」「年功序列」という擬似的な“家族制度”の中で、個より集団が尊ばれた。

「みんなで汗を流すことが、成功の証」

そこには個人主義とは異なる“和”の倫理があった。

ただし、この共同体意識は1990年代以降に急速に解体し、いま「昭和っぽい」と言われる象徴的な懐かしさを生んでいます。

三、人情と義理 ― 「情けは人のためならず」

昭和の街には、まだ「顔の見える社会」があった。

八百屋、銭湯、近所の世話焼き――

“縁”と“情”が社会の潤滑油であり、口約束が信用となった時代。

「人は理屈よりも情で動く」

そうした情の連鎖が、経済と文化を温かく支えていた。

この“人間臭さ”こそが、いまSNSの匿名社会に疲れた若者たちに「昭和っぽい優しさ」として再評価されているのです。

四、匂いと音 ― アナログのぬくもり

「昭和っぽい」は、実は“感覚”でもあります。

畳の青い香り、白黒テレビのちらつき、銭湯の石けんの匂い、ラジオのノイズ。

どれもデジタルでは再現できない物質の記憶です。

「手で触れることが、実在を確かめる方法だった」

便利になった令和の暮らしの中で、アナログへの郷愁が“昭和らしさ”として蘇るのは、人間の感覚がまだ完全に電子化していない証拠でしょう。

五、夢と現実の混線 ― 「不器用な誠実さ」

昭和の人は「かっこよく生きる」より、「まっすぐ生きる」を選んだ。

恋愛も友情も、嘘がつけない不器用さがあった。

不完全なまま努力し、泥臭くも一途に進む――その姿が、いま再び「昭和っぽい」と形容される所以です。

「完全ではないが、誠実だった」

― それが昭和的ヒューマニズムの核心。

結語 昭和っぽいとは、魂がアナログであること

「昭和っぽい」という言葉の根底には、不完全さを受け入れる美学があります。

AIが完璧な計算をする時代に、人間の“間違い”遠回り”ため息”を愛おしいと思える感性。

それこそが、令和の私たちがもう一度取り戻すべき“人間の温度”なのかもしれません。

――What Does “Showa-esque” Mean?――

The year 2025 marks the 100th year of the Showa era.

As part of this year’s project, we’ve held a total of seven gatherings to trace back through the 100-year history of Showa, and today at 6 p.m. will be our final session.

From 1995 all the way to 2025—the final 30 years—we’ll cover them all in one go.

Personally, in this milestone year, revisiting and studying the formation of Japan as a nation has been incredibly valuable. I’ve gained a deeper understanding of terms such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement, and the so-called “Deep State.”

Showa began when Japan, after World War I, joined the League of Nations and was recognized as a major power on the global stage. But a hundred years later, generations have changed, and with them, so much else.

Even today, people say something feels “Showa-esque.”

But what exactly was the essence of the Showa spirit?

I’ve given it some thought.

People of the Showa era believed that accepting and enduring unfairness was a sign of strength.

At work, there were the boss’s shouts; at school, the teacher’s bamboo stick; at home, silent fathers.

Behind it all, however, was a shared determination: to survive as a cog in society’s great machine.

“Injustice is merely another form of training.”

With that belief, they built Japan’s infrastructure and technological foundation through sheer effort.

This “culture of endurance,” often criticized today, actually served as a kind of psychological immune system that maintained social order.

The Showa-era salaryman was literally called a corporate warrior.

Work came before family. Within the pseudo-family systems of lifelong employment and seniority-based hierarchy, the group was valued above the individual.

“Sweating together is the proof of success.”

This was a moral code rooted in wa—harmony—distinct from Western individualism.

Yet, since the 1990s, that sense of community has rapidly dissolved, leaving behind the nostalgic warmth now referred to as “Showa-esque.”

In Showa-era neighborhoods, society still had a face.

The greengrocer, the public bathhouse, the meddling neighbor—

relationships and empathy were the lubricants of daily life, and a verbal promise was as good as a contract.

“People are moved more by feeling than by logic.”

This chain of human warmth sustained both the economy and culture.

It is precisely this “human touch” that young people, weary of today’s anonymous social media age, are now reappreciating as the gentle warmth of “Showa kindness.”

“Showa-esque” is, in truth, a sensory experience.

The green scent of tatami mats, the flicker of a black-and-white TV, the soap smell of a public bath, the crackle of radio static—

these are memories embedded in physical matter that digital technology can’t replicate.

“Touching something with your hands was how you confirmed it was real.”

In our hyper-convenient Reiwa lifestyles, the nostalgia for the analog reflects a simple truth: our human senses have not yet been fully digitized.

People of the Showa era chose to live not “coolly,” but “honestly.”

In love and friendship alike, they were awkward, unable to lie.

They struggled, worked hard, stumbled, and kept moving forward—

and that unpolished sincerity is precisely what we now describe as “Showa-esque.”

“Not perfect, but genuine.”

That is the heart of Showa humanism.

At its core, the phrase “Showa-esque” contains an aesthetic of imperfection.

In an age where AI calculates with perfect precision, it’s the ability to cherish human mistakes, detours, and sighs that keeps us truly alive.

Perhaps that is the “warmth of humanity” we, in the Reiwa era, must rediscover once again.

理不尽が思考を止めるとき

――『チ。』を観て

帰国後の夜、以前漫画で読んだ

『チ。―地球の運動について―』をネットフリックスでアニメーションで観た。

サカナクションの「怪獣」。天才的な音楽で、一度も早送りせずに聞きましたが、そのテーマとともに、死を賭けても真理を追求したいと思う登場人物たちの気持ちに、胸の奥がじんと熱くなった。

思えば、理不尽なことほど、人間の思考とやる気を止めるものはない。

どんなに努力しても報われない。

どんなに正しくても認められない。

そんな現実に直面すると、誰もが無意識に「考えること」をやめてしまう。

けれど、歴史を振り返れば、理不尽の中でなお考え続けた人たちがいた。

彼らは沈黙ではなく、知をもって抗い、やがて時代を動かした。

『チ。』の登場人物たちは、その象徴のように見える。

今の政治を見ていると、あまりにも理不尽だと感じる。

説明のない政策、責任の所在が曖昧な決定、それらは人々の思考を奪い、無力感を植えつける。

だからこそ、高市首相の支持率が80%を超えるような事態になっている。

次の時代は「理」を取り戻す政治でなければならない。

理にかなう判断、理に基づく議論、理をもって人を導くこと。

それが、本来あるべき知のあり方だと思う。

理不尽の時代を越え、「理」の時代へ。

その始まりは、ひとりひとりが再び「考えること」からだ。

—After Watching Chi: On the Movements of the Earth

One night after returning to Japan, I watched Chi: On the Movements of the Earth on Netflix—an animated adaptation of the manga I had once read.

The theme song, “Kaiju” by Sakanaction, was sheer genius. I listened without skipping a single second. As the song played, I felt a quiet heat in my chest, stirred by the characters who were willing to risk their lives in pursuit of truth.

When I think about it, nothing stops human thought and motivation more completely than the absurd.

No matter how hard you work, you may not be rewarded.

No matter how right you are, you may not be recognized.

When faced with such reality, anyone would unconsciously stop thinking.

And yet, if we look back through history, there were always those who kept thinking even amid absurdity.

They did not choose silence—they resisted with knowledge, and in time, they changed the course of history.

The characters in Chi seem to embody that very spirit.

Watching today’s politics, I cannot help but feel the same sense of absurdity.

Policies are made without explanation.

Decisions are taken with no clear sense of responsibility.

Such actions rob people of the will to think and plant a deep sense of helplessness.

Perhaps that is why Prime Minister Takaichi’s approval rating has exceeded 80 percent.

The next era must be one in which reason is restored to politics—

decisions grounded in reason, debates guided by logic, and leadership founded on understanding.

That, I believe, is the true nature of knowledge.

Beyond an age of absurdity, toward an age of reason.

It all begins when each of us chooses, once again, to think.

藤本幸弘の英文論文集作っています。

この3年間は、2000年から2020年、50歳までに書き続けてきた「レーザー治療」や「レーザー工学」とは異なった分野。

AI教育法や、ゴルフスイング物理学、NMN、音楽が脳と身体に与える影響。

この辺りの論文が増えました。

I am currently compiling a collection of my English papers written by Yukihiro Fujimoto.

Over the past three years, my research has expanded into new fields, different from the areas I had focused on up until the age of fifty — namely, “laser therapy” and “laser engineering,” which I had continuously studied from 2000 to 2020.

Recently, my papers have increasingly explored topics such as AI-based educational methods, the physics of the golf swing, NMN, and the effects of music on the brain and body.

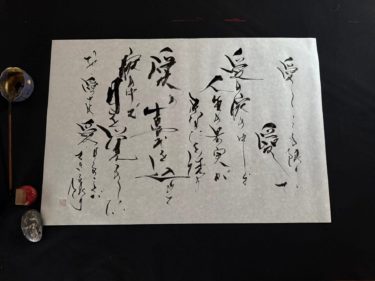

今日はスタインウェイの自動演奏ピアノに合わせて、書家・白石雪妃さんが筆を走らせる瞬間を映像に収めました。ゴルフ医科学研究所スタッフ含め、撮影部隊、総勢5名。

選んだ曲はショパンの《革命》《ノクターン》《英雄ポロネーズ》、そしてリストの《ラ・カンパネッラ》《愛の夢》の5曲。

ピアノの響きと墨の流れが呼応し、まるで音が線となって紙の上に舞い降りるような時間でした。

一音ごとに筆先が息づき、旋律が視覚化されていく。その融合の美は、まさに「音が書となる瞬間」。

映像とともに、音と書が共鳴したこのひとときをWEBに整理して公開します。ぜひご覧ください。

Today, we captured on film the moment when calligrapher Yukihi Shiraishi let her brush dance in harmony with the music of a Steinway self-playing piano.

Including the staff from the Golf Medical Science Institute, our filming crew consisted of five members in total.

The selected pieces were Chopin’s Revolutionary Étude, Nocturne, and Heroic Polonaise, along with Liszt’s La Campanella and Liebesträume — five works in all.

The resonance of the piano and the flow of ink responded to one another, creating a moment when sound seemed to take form as lines, descending gracefully onto the paper.

With each note, the brush came alive, and the melodies took visual shape. The beauty of this fusion was truly “the moment when sound becomes calligraphy.”

We will be sharing this special moment — where sound and calligraphy resonated together — as a video presentation on our website. Please take a look.