健康寿命と長寿寿命は別モノだった:日本の地域差を読む

「日本は長寿国である」

この言葉に、どれだけの実感がこもっているだろうか。

長く生きる。

しかし、その時間は「健康」なのか?

それとも、誰かの手を借りなければならない「寿命」なのか。

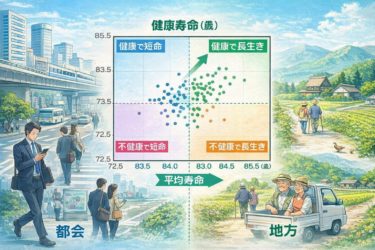

今回は、都道府県別に見る「平均寿命」と「健康寿命」のズレから、人生の質を決める「生活の構造」を見つめてみたい。

「健康寿命」と「平均寿命」は違う

平均寿命:何歳まで生きるか(死亡統計)

健康寿命:どこまで「自立して生きられるか」(日常生活に制限がない期間)

日本人は、平均すると

男性:約9年

女性:約12年

を「不健康な状態」で過ごしていることになる。

そのギャップを埋めるカギは何か。

医療ではなく、「生活構造」が寿命を決めている

この言葉が、今回の本質である。

平均寿命を伸ばすのは…

医療の介入

薬の処方

延命技術や制度

健康寿命を伸ばすのは…

毎日の運動

社会参加

適度な医療

心のゆとり

つまり、健康寿命は「日々をどう生きるか」にかかっている。

これは医療の世界に身を置く者としても、痛烈な事実だ。

どんなに高価な医療機器があっても、毎日を健やかに生きる力を直接“注入”することはできない。

都会 vs 地方:どちらが健康か?

都市には最新の医療機関が揃い、情報も人も溢れている。一見、健康寿命にも有利な環境のように見える。だが、統計は違う顔を見せている。

都市部の実態:

移動は車か電車。歩かない。

隣人と顔を合わせることがない。孤立。

情報過多・交感神経優位な生活。

労働ストレスと医療過信。

これでは、健康寿命は延びない。

地方の強さ:

日常的に体を動かす環境(農作業・坂道・買い物)

家族構造が残り、会話も多い

「役割」が地域にある

医療は必要なだけ、過剰ではない

そして何より──

“無理をしないで生きられる経済設計”

(例:生活コスト、地代、税率)が成立している。

これは都市部での“頑張らなきゃ生きていけない構造”と対照的である。

本当の意味で「長生き」とは

医療の世界ではよく「延命」について議論される。

だが、平均寿命をいくら延ばしても、健康寿命が伴わなければ、生きている時間が「人生」になるとは限らない。

健康寿命を延ばすとは、「余生」ではなく「現役時間」を伸ばすこと。社会に関わり、役割を持って、自分で歩いていく時間を、1年でも長くすること。

もし本気で国や地域が「健康長寿」を目指すなら、すべきことは明らかだ。

医療へのアクセスより、「歩く道」を作ること

薬よりも、「話し相手」を増やすこと

高齢者施設よりも、「地域に居場所」を用意すること

そうすれば、平均寿命ではなく、健康寿命が延びていく。

「何歳まで生きたか」よりも、「どう生きられたか」を、私たちはもっと見つめるべき時代に入っている。

長寿国家・日本の真の課題は、その“長さ”に“質”を加えることだろう。

Healthy Life Expectancy and Longevity Are Not the Same: Reading Japan’s Regional Differences

“Japan is a long-lived nation.”

How much lived reality is actually contained in that phrase?

Yes, people live long.

But are those years lived in good health?

Or are they years of mere survival—years that require constant assistance from others?

In this essay, I would like to examine the structure of daily life that determines quality of life, by looking at the gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy across Japan’s prefectures.

Healthy Life Expectancy vs. Life Expectancy

Life expectancy: how long people live (based on mortality statistics)

Healthy life expectancy: how long people can live independently, without limitations in daily activities

On average, Japanese people spend:

about 9 years (men)

about 12 years (women)

in a state of poor health.

What, then, is the key to closing this gap?

Not Medicine, but the Structure of Daily Life Determines Longevity

This is the core message.

What extends life expectancy:

medical intervention

prescription drugs

life-prolonging technologies and systems

What extends healthy life expectancy:

daily physical activity

social participation

appropriately limited medical care

mental and emotional breathing room

In other words, healthy life expectancy depends on how we live each day.

This is a painful truth, especially for those of us who work in medicine. No matter how advanced or expensive medical technology becomes, it cannot directly inject the ability to live well into people’s daily lives.

Cities vs. Rural Areas: Which Is Healthier?

Cities are filled with cutting-edge medical facilities, information, and people. At first glance, they seem advantageous for healthy longevity. Yet the statistics tell a different story.

The reality of urban life:

Movement by car or train—little walking

Rarely seeing or speaking with neighbors—social isolation

Information overload and chronically heightened sympathetic nervous activity

Work-related stress and overreliance on medical care

Under these conditions, healthy life expectancy does not increase.

The strengths of rural areas:

Environments that naturally encourage daily movement (farming, hills, walking to shops)

Family structures that remain intact, with frequent conversation

Clearly defined social roles within the community

Medical care that is sufficient, but not excessive

And above all—

an economic structure that allows people to live without constant strain

(lower living costs, land prices, and tax burdens).

This stands in stark contrast to the urban structure in which “you have to keep pushing yourself just to survive.”

What “Living Long” Really Means

In medicine, we often debate life prolongation. But no matter how much we extend life expectancy, if healthy life expectancy does not follow, time alive does not necessarily become life.

Extending healthy life expectancy means extending not “old age,” but one’s active years—years in which people remain socially engaged, have roles to play, and can walk forward on their own feet, even if only for one more year.

If nations and regions are truly serious about achieving healthy longevity, the path forward is clear:

Build walkable paths, not just access to hospitals

Increase people to talk to, not just prescriptions

Create places of belonging in the community, not just elder-care facilities

Do this, and it is healthy life expectancy—not just average lifespan—that will grow.

We are entering an era in which we must look more closely at how people lived, not just how long.

Japan’s true challenge as a long-lived nation is to add quality to that length.